My path to linguistics at IU began at the Pondicherry University international students’ hostel in southeast India in 2012. I had been living there for three months with two dozen other undergraduate study abroad students, and two brothers, Joey and Moses Thangal, had become close friends of ours while serving as “hostel wardens.”

“Hey, Tricia,” Moses said, as we swatted away mosquitos one evening on the hostel’s front porch, “you know, in the village Joey and I are from, our mother tongue doesn’t have a written script. You study linguistics — can you come write one for us?”

In an instant, a monumental task lay before me. I realized it even then as a 21-year-old linguistics undergrad – and that an unwritten dissertation — if not a full career — had just materialized out of thin air.

The Thangal tribe, as I learned over the next few years, comprises approximately 1,200 members spread throughout just under a dozen villages in the far northeast Indian state of Manipur — as the crow flies, a full 1,300 miles from our Pondicherry hostel. As is the case with many languages of this region, Thangal is a severely under-documented and under-resourced Tibeto-Burman language; the few published sources for Thangal language data date back primarily to the 1800s. As English spreads, Thangal community members recognize the threat to their native language and are actively trying to document and preserve it.

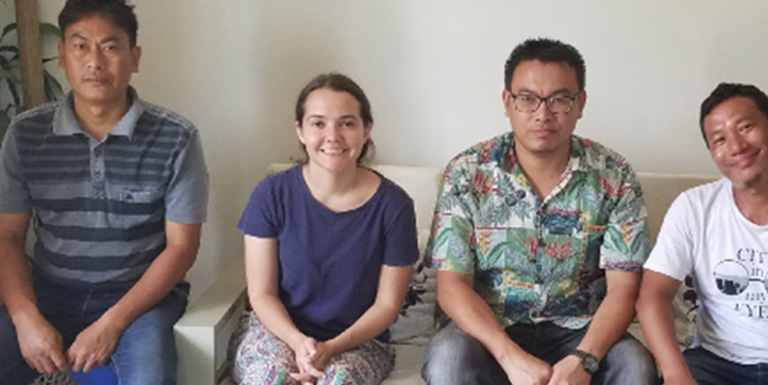

With generous support from IU and the American Institute of Indian Studies, I’ve made multiple fieldwork trips to Manipur, the most recent being a seven-month stay from January to August of 2019. These trips have allowed me to celebrate marriages and births in the village; sample local fermented fish; and experience the effects of multiple road strikes, when the national highway that runs through the village becomes eerily deserted. Most importantly, my fieldwork has enabled me to interact with dozens of members of the community; gather a wealth of recordings of conversations, folk tales, and translations; and gain valuable insight into a language for which so little is published. So far, I have presented my findings at the 171st meeting of the Acoustical Society of America, the Endangered and Lesser Known Languages conference in India, and the Himalayan Languages Symposium in Sydney.

Eight years, three additional trips to India, and hundreds of pages of data later, I look back on that initial conversation on the hostel porch with awe and appreciation for the journey that was (and still is) to come. As I continue working toward my dissertation — a descriptive work on Thangal focusing on topics in phonetics and morphosyntax — I am eager to continue contributing to an ongoing academic discussion on the languages and cultures of under-represented tribal communities in Northeast India, and directly helping the Thangal community preserve its mother tongue.

The College of Arts

The College of Arts